Forecast calls for... cardiac arrest? The Weil Institute interviews Dr. Takahiro Nakashima

In the February edition of the Weil Institute newsletter, we introduced Takahiro Nakashima, M.D., PhD, a research fellow in the department of Emergency Medicine and recipient of the American Heart Association's Max Harry Weil Award for Resuscitation Science.

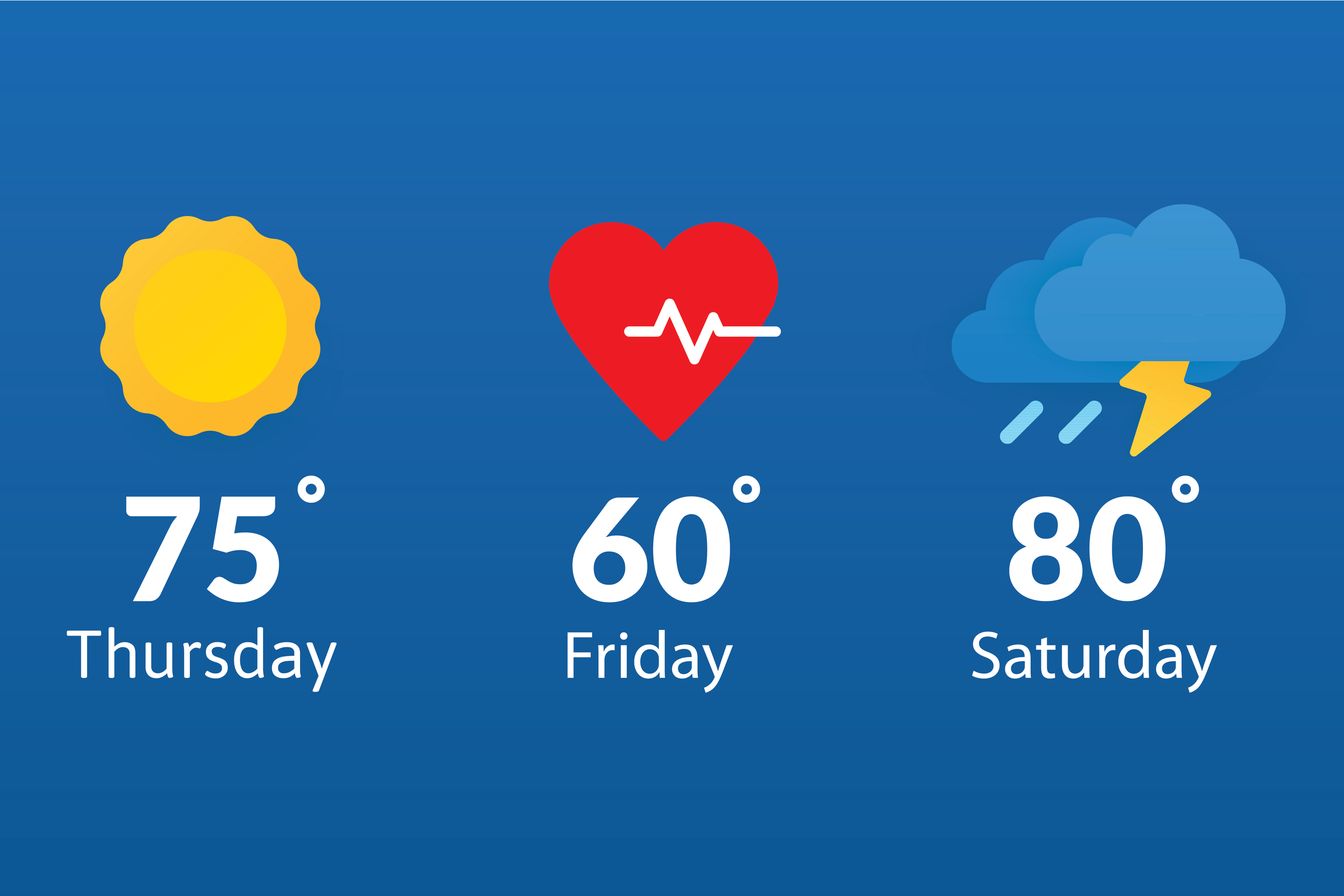

This month, the Weil Institute met the Weil award winner as we sat down to discuss Dr. Nakashima's research including... using time and weather to predict out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence? Keep reading to learn more!

Q: Thank you for joining us, Dr. Nakashima! Before we dive in, can you tell us a little about yourself and your work at Michigan Medicine?

A: I am a cardiologist at the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center in Suita, Japan. I came to Michigan Medicine in August of 2020 to work with Dr. Robert Neumar, who I met at the Japanese circulation society annual symposium six years ago. I am now a research fellow with the Michigan Resuscitation Innovation and Science Enterprise (M-RISE), where I am working with cardiac arrest models and a registry of population studies.

Q: What do you enjoy most about your field of research?

A: One exciting aspect of resuscitation science is the range of topics being discussed. We are not just looking at the heart, but also the brain. It’s a field that any background can join and can bring a variety of ideas and perspectives to.

It’s also thrilling to think of how our research will one day affect real practice. I am examining the effect of treatments in models of prolonged cardiac arrest, and it’s always very exciting whenever I can bring a model back from arrest.

Q: Your research “Machine Learning Model for Predicting Out-of-hospital Cardiac Arrests Using Meteorological and Chronological Data” received the American Heart Association’s Max Harry Weil Award for Resuscitation Science. Can you tell us more about this project?

A: In clinical practice, we see more cardiac arrests on cold days. We also know that—in the United States, for example—there is an increase in cardiac arrests on New Year’s Day and during Daylights Savings. I wanted to find out if this information could be used to predict out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA).

For this project, my team and I conducted a population-based study that combined a nationwide registry of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest cases and high-resolution meteorological and chronological datasets from Japan. We found that the model that combined both time and weather data had the highest predictive accuracy (up to 90%!) compared to models that used these variables separately.

Now, we are updating our model using CARES, a registry of OHCA cases from across the United States. This will give us the additional detail and granularity we need to apply the model in real-world applications. Our goal is to use this research to develop a warning system that will inform citizens and EMS personnel on days that have a high risk of cardiac arrests incidence.

Q: What does this recognition from AHA mean to you and your team?

A: It is very meaningful to us that this model was recognized by AHA. Patients who suffer cardiac arrest don’t always have prior reasons for visiting the doctor. We need to take account of not only personal risk factors but also environmental factors. And we need to intervene at every stage—prevention, education, EMS system/response, care, and rehabilitation.

Q: The Weil Institute accelerates critical care research from the idea stage to real applications in patient care. What do you predict will be some of the biggest critical care innovations in the next five or ten years?

A: In the next few years, I see us developing a new heart and neuroprotective drug that can be used by lay responders, a new mechanical circulatory support system that physicians can implement easily, and an automatic delivery system for AED and several drugs.

A major problem of cardiac arrest is that the first person at the scene usually isn’t a medical professional: it is a family member, or a coworker, or a stranger. This person might not be confident enough to do CPR, or they might not know where an AED is or how to use it. They might also be upset or rushing. With new tools, lay rescuers can assist calmly and confidently wherever a cardiac arrest occurs.